Atlas of Congenital Cardiac Disease, by Dr. Maude E. Abbott

Organization: Musée régional d’Argenteuil

Coordinates: www.museeregionaldargenteuil.ca

Address: 44, route du Long-Sault, Saint-André-d'Argenteuil, QC J0V 1X0

Region: Laurentians

Contact: Lyne St-Jacques, info(a)museearg.com.

Description: First edition of the Atlas of Congenital Cardiac Disease by Dr. Maude Elizabeth Seymour Abbott.

Year made: 1936

Made by: Published by The American Heart Association

Materials/Medium: Paper

Colours: Red cover, black and white pages

Provenance: New York

Size: 27.9 cm x 35.56 cm x 1.27 cm

Photos: Rachel Garber. Courtesy Musée regional d’Argenteuil

Dr. Maude Elizabeth Seymour Abbott (1869-1940)

Brenda Hartwell

“Aim at the highest and you will arrive at something above mediocrity, aim at mediocrity, and you will fall below it.” This quote was discovered in the margin of Maude Abbott’s Botany book, dated September 28, 1887. She was 18 at the time, and this maxim served her well. Against all odds, this shy, brilliant woman rose to prominence in the male dominated world of medicine and became a world-renowned heart specialist.

Seven months after her birth on March 18, 1869, Maude lost her mother to tuberculosis. Maude’s father, Jeremiah Babin, had abandoned his family, so Maude and her sister Alice were raised by their maternal grandmother, the widow of the Reverend William Abbott, rector of the small parish of St. Andrews East, Quebec.

“A stereotypical Scot, Mrs. Abbott was dedicated to the tradition of education and culture” (Waugh, p. 25) and a governess was employed to teach the girls on the subjects of Literature, French and History. By all accounts, Maude relished intellectual pursuits and dreamed of attending a real school. That wish was granted when she was sent to Misses Symmers and Smith’s private academy in Montreal. On completion of this year, Maude wrote the McGill examinations for Associate in Arts and won a scholarship from her school. “It was still unusual for women to go into any branch of higher education other than to Normal School, to become teachers”… “The university (McGill) had admitted its first women students in Arts in 1884, only two years before Maude applied” (Waugh, p. 27).

In 1890, Maude not only graduated from McGill, she was class valedictorian and won the Lord Stanley Gold Medal for general proficiency. She hoped to study medicine at McGill, but she met severe resistance. Dr. F.J. Shepherd stated, “it would be nothing short of a calamity, and Dr. G.E. Fenwick declared he would resign if women were admitted” (Abbott, 1997). Fortunately, Bishop’s College, which had been operating a medical school in Montreal since 1871, decided to open its medical program to women and invited Maude to attend. “Maude graduated brilliantly in June of 1894, taking the Senior Anatomy Prize and the Chancellor’s Prize” (Waugh p. 45).

Following an eclectic period of post-graduate studies in Europe where she studied under some of the world’s finest doctors, Dr. Abbott returned to Montreal and established a private practice on Mansfield Street. Dr. Charles Martin invited her to work on the subject of cardiac lesions, in the recently opened Royal Victoria. Dr. Abbott was slowly making inroads into this male dominated world, but her struggles were not over. Her first cardiological research paper, a clinical study of “Functional Heart Murmurs,” was presented for her at the Medico-Chirugical Society by Dr. James Stuart because women were not allowed membership in the Society. The paper was well received and published in the Montreal Medical Journal, 1899 (Abbott, p. 55).

Following the death of her grandmother, Dr. Abbott became responsible for her sister Alice, who suffered from a mental condition. Dr. Abbott arranged for continuous care in their home at St. Andrews, and returned there most weekends. The financial burden would have been considerable, considering Dr. Abbott's meagre income.

In 1898, Dr. Abbott was appointed Assistant Curator of the McGill Pathology Museum, and it flourished under her hand. Dr. Abbott's enthusiasm, intellectual curiosity and drive were almost boundless. Indeed, her contemporaries remarked that she could become so engrossed in a project that she would forget to eat and would barely sleep. She organized the museum’s collection and began to use the specimens as teaching tools. Her unofficial course of instruction was remarkably popular, and it became a compulsory part of the curriculum for two decades.

While at the museum, Dr. Abbott worked closely with the renowned Dr. William Osler to complete information on the abnormal heart specimens in the Osler collection. Her work was meticulous and painstaking. Osler, “recognizing the value of their partnership to the world of science and to his reputation, immediately lent his prestige and his financial support to the work.” In a letter to Dr. F.J. Shepherd in 1905, he stated, “She evidently has a genius for this sort of thing.”… “I do not believe there is a museum in Great Britain with a better collection—there is nothing like it on this side” (Waugh p. 60).

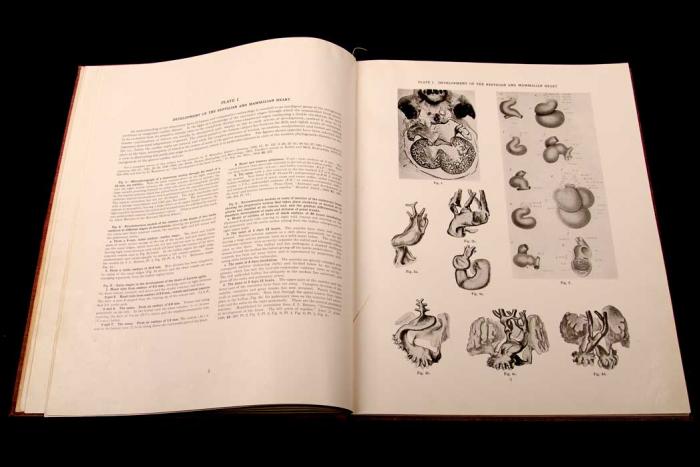

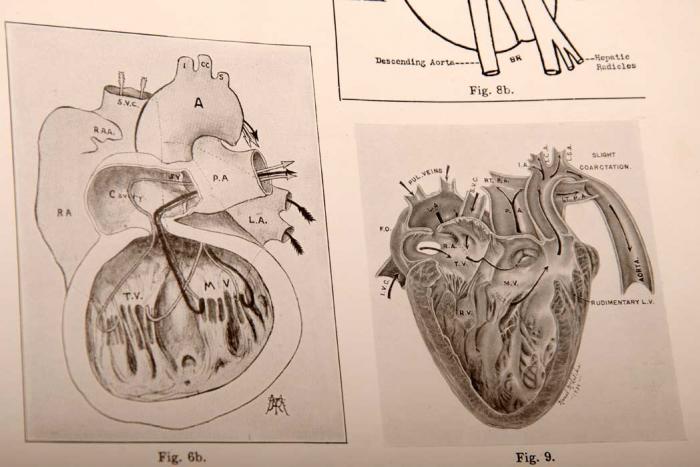

Dr. Osler invited Dr. Abbott to write the section on congenital cardiac disease for his forthcoming book, System of Modern Medicine. When the work was completed in December 1907, Osler wrote, “It is by far and away the very best thing ever written on the subject in English—possibly in any language.” Dr. Abbott continued her work on this subject, and her Atlas of Congenital Cardiac Disease, published in 1936, when surgical correction of some congenital conditions was beginning, became the last word on the subject, and remained so for many years” (Scriver, p.155).

It would be impossible to list all the accomplishments of this woman, nicknamed “The Beneficent Tornado” by one of her peers. She was instrumental in forming the International Association of Medical Museums in 1906, and established and edited their Bulletin. Also, she was a founder of the Federation of Medical Women of Canada in 1924, and a champion of higher education for women. But her indestructible memorial is her work on congenital heart disease.

This artefact, the first edition of the Atlas of Congenital Cardiac Disease published in New York by The American Heart Association, is an oversized hardcover book, 27.9 cm wide by 35.56 cm tall and 1.27 cm thick. It represents a lifetime of research and was considered “the bible” by heart surgeons for decades.

Although Dr. Abbott's work was respected around the globe, full professorship at McGill was never bestowed upon her. Nevertheless, she passionately pursued her work and provided a brilliant example to her contemporaries in the province of Quebec, proving that women could not only succeed—they could excel— in hitherto male dominated fields. She paved the way for future generations of women, and countless survivors of heart surgery owe their life to her research.

Sources

Douglas Waugh, M.D. Maudie of McGill: Dr. Maude Abbott and the Foundations of Heart Surgery, Toronto and Oxford: Hannah Institute & Dundurn Press, 1992.

Elizabeth Abbott, All Heart: Notes on the Life of Dr. Maude Elizabeth Seymour Abbott, M.D. Pioneer Woman Doctor and Cardiologist, Saint Anne de Bellevue: 1997.

Dr. Margaret Gillett, “The Beneficent Tornado,” Unpublished lecture given to the Sherbrooke & District Women’s Canadian Club, February 8, 1977.

Maude Abbott Medical Museum. McGill University. http://www.mcgill.ca/medicalmuseum/introduction/history/physicians/abbott/

Musée régional d’Argenteuil. http://www.museeregionaldargenteuil.ca

To Learn More

Library and Archives Canada: Maude Abbott, www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/women/030001-1401-e.html

Maude Abbott Medical Museum, www.mcgill.ca/medicalmuseum

Author

Brenda Hartwell is a writer and editor. She lives in Quebec's Eastern Townships.

Add new comment