Chinese Dragon

Organization: Montreal Chinese Community & Cultural Centre

Coordinates: www.ccccmontreal.com

Address: 1088 Clark Street, Room 300, Montreal, QC H2Z 1K2

Region: Montreal

Contact: Anna Xu, Manager, comments(a)ccccmontreal.com

Description: The Chinese dancing dragon is a soft sculpture with a painted wooden head. It is used in celebration of special occasions and holidays, and symbolizes prosperity and good fortune. It is carried by at least 10 dancers who grasp bamboo posts projecting from the underside of the 50-foot dragon. It was a gift to the Montreal Chinese Community & Cultural Centre from the Government of China.

Year made: circa 2008

Made by: Unknown. Made for the Government of China.

Materials/Medium: Polyester, silk, wood, paint

Colours: Green, red, yellow, pink, black, white, etc.

Provenance: Beijing, China

Size: approx. 15.5 m x 1 m x 70 cm

Photos: Rachel Garber. Courtesy Montreal Chinese Community & Cultural Centre

The Chinese Communities of Quebec

Doris Ng Ingham

Finding one single object to represent the Chinese in Quebec is a difficult task as there is not one Chinese community, but many Chinese communities with different backgrounds, histories and cultures. One symbol of all Chinese people however, is the dragon, a mystical creature that has captured the imagination of people throughout history.

The Chinese dragon is portrayed as a long animal with four legs. Unlike Western culture, it is not an animal to be feared, but rather a noble symbol of good fortune, benevolence, perseverance and strength which is sometimes used to refer to Chinese people themselves. If we look at Sino-Quebec history in the province, the dragon will justify this self-depiction as Chinese people struggled through history in the search of a better life, despite obstacles such as languages barriers, discrimination and conflicts.

The First Wave

The first major wave of Chinese citizens arrived in Quebec in the late 1880s. They were young men of modest means from the southern countryside of China, each of them speaking a variant of the Cantonese language. They were fleeing an impoverished and unstable China and believed that they were heading to the “American Eldorado” known to them as “Gold Mountain.” Needless to say that once in the country, this idea of a land of plenty vanished. Most of them found work on the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway and after its completion, they became involved in the restaurant or laundry business.

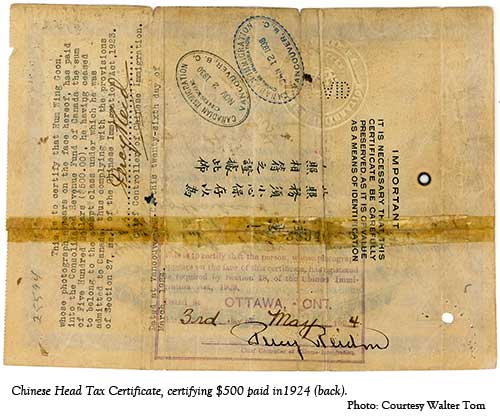

In order to reduce an influx of Chinese arriving in Canada, the Canadian government introduced a series of immigration policies directed solely at this cultural group. In 1885, the Canadian government passed the first of a series of laws requiring Chinese immigrants to pay an entry fee, or "head tax." The Head Tax forced newcomers to pay exorbitant entry fees ($500 in 1903, the price of two houses at the time).

As of 1923, Canada decided to completely close the door to Chinese immigration. Both laws and racism contributed largely to the creation of a secluded society of single Chinese men. It was not until 1947 that the government allowed this population to enter the country again and let families be reunited. In 2006, those who were still alive from this time period, or their surviving wives, were granted partial redress as well as receiving an official apology from the federal government for past discriminatory measures aimed directly at them.

Incidentally, language and religious barriers were additional issues in Quebec. Prior to Bill 101, a great number of Allophones including the Chinese were attending English-speaking schools.

Catholic French-speaking schools refused to admit non-Catholic children and in some cases, turned them away even if they agreed to convert to Catholicism. At the time, Francophones were not oriented toward integrating Allophones. Additionally, there was a strong sense of preserving the status quo of the French-speaking population. This spurred the Sino-Quebecers towards the English-speaking population.

This chapter of history stretched over half a century and was marked by important challenges which paved the way for the integration of future generations of migrants.

Successive Waves of Chinese Immigration

Another wave of Chinese immigrants, with very different roots from the first wave, landed in Quebec from Indochina in the late 1970s into the early 1980s, benefiting from special refugee programs put in place by the Canadian government. This time period coincided with the fallout from the Vietnam War, which resulted in the arrival of “boat people” and refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos; amongst them a significant number with Chinese origins.

An interesting fact about these immigrants is that many had the ability to converse in French as they were part of former “French Indochina” colonies. Once integrated in their adoptive country, they joined the larger Chinese community, but would later form their own cultural organizations such as the Sino-Vietnamese association and the Sino-Cambodian association, as they had their own history and culture that differed from the Chinese immigrants. In terms of languages, despite widely speaking Vietnamese, Cambodian or Lao, they could also converse in Cantonese and/or Mandarin.

The 1980s and 1990s saw a massive immigration movement from wealthy and well-educated Hong Kong people because of the uncertain climate in China in the aftermath of Tiananmen Square and the return of Hong Kong to China in 1997. In addition, the mid-80s saw the Canadian government introduce the “Business Immigration Program” which prompted the immigration of entrepreneurs from this former British colony.

Immigration reached its peak in 1994 and then started declining as the economic crisis deepened in 1995. This influx of immigrants was bilingual in both English and Chinese and came from a lineage different from the previous two waves of immigration, although many could find their roots in southern Guangdong. They introduced a more flamboyant and sophisticated culture, were business-oriented and contributed greatly to the establishment of Cantonese-speaking schools in Quebec.

Currently, the newest wave of immigrants is from mainland Mandarin-speaking China. In 1989, the government of Canada allowed students to immigrate and in the 1990s, immigration expanded because of Canada’s greater emphasis on admitting economic or “business category” immigrants from China’s growing middle class who had increased capital and financial assets. Since then, there has been a profound shift in the “Chinese-Quebecer” landscape. These newcomers seem to ignore past Chinese-Canadian history and the struggles faced by their predecessors.

Subsequently, many Chinese communities, as they do not represent one unified community, coexist, but do not mingle as a result of the discrepancies in culture, language and history.

This is well illustrated in the documentary “Being Chinese in Québec: A Road Movie,” directed by Malcolm Guy and William Ging Wee Dere. The film discusses the issues of the Canadian immigration policies as well as the origins of the Chinese population in the province and the search for identity from the younger generation. The first Chinese-Canadian settlers experienced very different challenges from following generations.

Similar to a Chinese dragon, the Sino-Quebecker communities persevered and were resilient when confronted with demanding and difficult times.

Sources

Daniel M. Goodkind, “Creating New Traditions in Modern Chinese Populations: Aiming for Birth in the Year of the Dragon,” Population and Development Review. December 1991: 663-686. Jstor. February 25, 2013.

Gertrud and Lynn Clark Neuwirth, “Indochinese Refugees in Canada: Sponsorship and Adjustment,” International Migration Review. Spring - Summer, 1981: 131-140. Jstor. February 25, 2013.

Kwok Bun Chan, Smoke and Fire: The Chinese in Montreal. Shatin: The Chinese University Press, 1991.

Serge Granger, Le Lys et le Lotus: Les Relations du Québec Avec la Chine de 1650 à 1950. 2005.

Eve Haque, Multiculturalism Within a Bilingual Framework : Language, Race, and Belonging in Canada, 2012.

“Being Chinese in Quebec: A Road Movie,” Dir. Malcom Guy and William Ging Wee Dere. Productions Multi-Monde, 2013.

“My Ancestors’ House,” Dir. Suzette Lagacé. MOZUS Productions, 2009.

Bang San Hoe, “Folktales and Social Structure: The Case of the Chinese in Montreal.” Civilization.ca/research-and-collections/research/resources-for-scholars/essays-1/cultures/ban-seng-hoe/folktales-and-social-structure-the-case-of-the-chinese-in-montreal February 25, 2013.

To Learn More

Louis-Jacques Dorais, “The Cambodians, Laotians, and Vietnamese in Canada.” Collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/008004/f2/E-28_en.pdf February 25, 2013.

Library and Archives Canada. “Chinese Immigrants in Quebec Between 1910 – 1923.” Collectionscanada.gc.ca/chinese-canadians/021022-3000-e.html. February 25 2013.

Multicultural History Society of Ontario. “The Ties that Bind.” MHSO.ca. N.p.n.d. February 25, 2013.

Michel Parent, “Le Quartier Chinois Virtuel de Québec,” LeChinois.ca. N.p.n.d. February 25, 2013.

Vancouver Public Library. “Chinese Canadian Genealogy.” VPL.ca/ccg/index.html. February 25, 2013.

Chinese Immigrants in Quebec between 1910 – 1923. http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/chinese-canadians/021022-3000-e.html

Louis-Jacques Dorais, The Cambodians, Laotians, and Vietnamese in Canada. http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/008004/f2/E-28_en.pdf

Author

Doris Ng Ingham is a freelancer. She holds a B.Soc.Sc. joint honours in history and political science from the University of Ottawa. She also studied journalism at the Université de Montréal. She recently worked as a researcher on two feature-length documentaries: “Being Chinese in Quebec: A Road Movie” on the significance of Sino-Quebec identity, where she researched the history of Chinese-Quebecers and located this population throughout the province; and “My Ancestors’ House” a film on Chinese-Canadian self-identity and the practice of ancestral worshipping, where she looked into the history and traditions of the first wave of Chinese immigrants in Canada. Her professional career includes experience as a print and broadcast journalist, communication consultant, blogger and online community manager.

Add new comment