Lachine Canal Pay List

Organization: McCord Museum

Coordinates: www.mccord-museum.qc.ca

Address: 690 Sherbrooke Street West Montreal QC H3A 1E9

Region: Montreal

Contact: Cynthia Cooper, cynthia.cooper(a)mccord.mcgill.ca

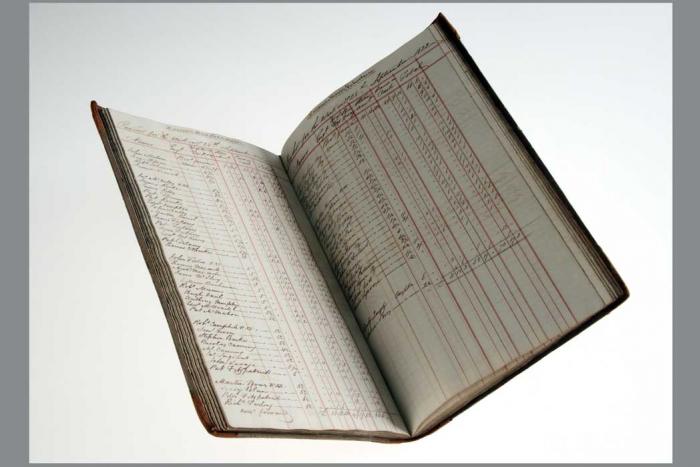

Description: Hand written ledger in which names and cash amounts for workers employed at the Lachine Canal were recorded.

Year made: 1822-1824

Made by: Unknown but “Pay Lists” is marked on the cover

Materials/Medium: Leather and paper

Colours: Brown with buff pages, red ink (faded)

Provenance: Quebec

Size: 34 cm x 21 cm

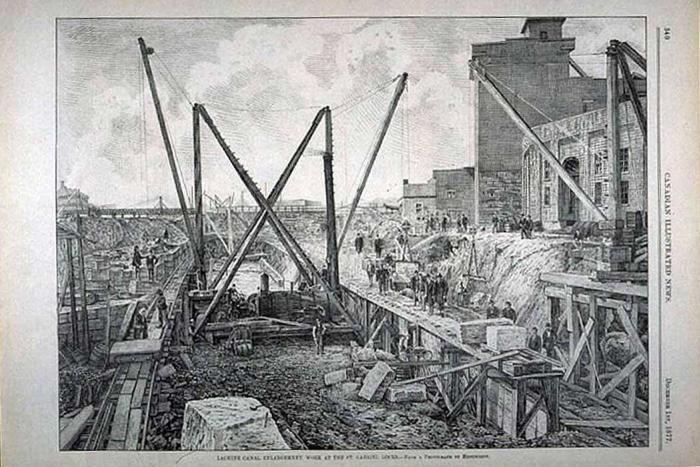

Photos: © McCord Museum: (1, 2) Lachine Canal Pay List, photo P070_A3.4.1; (3) Lachine Canal Enlargement – Work at the St. Gabriel Locks, December 1, 1877, 19th century drawing, ink on paper. Gift of Mr. Charles deVolpi, M979.87.441; (4) Entrance to the Lachine Canal, Montreal, QC, 1826. Photograph with glass lantern slide of watercolour by unknown artist, MP-1976.288.2.

Lachine Canal Pay List, 1822-1824

Rod MacLeod

For the growing traffic along the St. Lawrence River, Montreal was a bottleneck. The rapids just upriver from the town were dangerous enough to oblige ships to dock in the port, unload their goods, and ship everything by cart westward to the village of Lachine, where other boats waited to sail on to the Great Lakes. This elaborate process brought business for Montreal shopkeepers and the service trades, and especially for carters, but merchants called for the construction of a canal to bypass the rapids. After the Napoleonic wars, civic leaders renewed their promotional efforts, pointing to the colony’s need to compete commercially with the United States.

While the colonial government dithered over this question, Montreal merchants took the initiative in the spring of 1819 and created a Company of Proprietors. Although it would soon fold after failing to raise enough capital to begin construction, the company did lay the foundations for this crucial enterprise. The Proprietors commissioned British engineer Thomas Burnett and surveyor John Adams to map out the route the canal would follow, factoring in not only distances and ground quality but also the landowners whose property would have to be expropriated. Impressed by this efficiency, the government appointed and funded a commission in 1821 that would oversee construction of the canal.

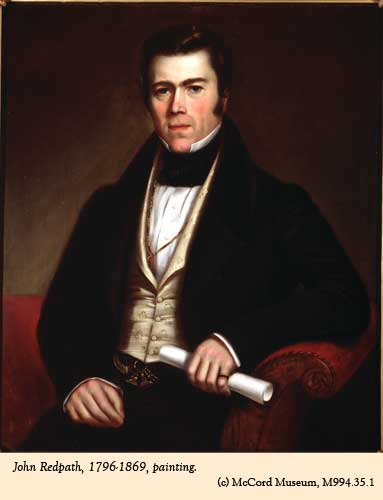

The contract to build the canal was awarded to master mason Thomas Phillips, who brought several men with whom he had previously worked into the project as subcontractors. Master carpenter Andrew White supplied the timber and oversaw the shoring up of the canal’s banks. Masons Thomas McKay and John Redpath provided the stone (from a quarry near Kahnawake) for the numerous locks, and organized their construction. Stanley Bagg, who had fingers in many lucrative pies, recruited and supplied the workers who dug the vast ditch and carried out all the other backbreaking jobs.

The Lachine Canal proved a career-maker for these contractors, particularly Phillips, McKay and Redpath, who would go on to supervise the construction of the Rideau Canal between the Ottawa River and Kingston. They would reinvest their fortunes in real estate: Redpath and Phillips developed extensive suburbs on the side of Mount Royal, while McKay would lay out the community of New Edinburgh near what would become the city of Ottawa. His house eventually became the residence of the governor general.

The 500-strong workforce assembled for the Lachine Canal project in 1821 was the largest in Canadian history up to that time, consisting largely of Irish Catholic immigrants along with a fair representation of French Canadians. Their names were recorded in registers, now in the possession of the McCord Museum. These registers consist of pay lists, showing what each man received in wages for a week’s work, with the total amount expended carefully noted at the bottom of each column.

In practice, these “wages” were token amounts that workers were obliged to spend on food, drink, clothing and other goods at the tavern and stores owned by Bagg’s brother Abner. Tavern and stores were located in the village of Lachine, where the workers were also housed during the construction period. After its completion in 1825, the canal continued to require a small workforce for general maintenance and to operate the locks. This, too, was gruelling work, involving long hours outdoors in all kinds of weather.

The Lachine Canal did allow traffic to move beyond Montreal without having to unload cargo, but it soon proved inadequate to the demand. By the 1840s, when the city was incorporated (the new municipal council included Phillips, Redpath and Bagg among its members) and the colony united under a new provincial parliament, the time had come to give the canal an overhaul, substantially widening it and improving the flow of water. This work was barely finished before Canada was plunged into a severe recession from which it did not emerge until the early 1850s. By that time, the railway was promising a more dynamic future for moving people and goods than the one represented by boats and canals.

Despite its important role in facilitating transportation from the western commercial hinterland to the lower St. Lawrence River, the Lachine Canal’s true significance lies in the water pressure flowing through it near the heart of nineteenth century Canada’s largest city. The late 1840s depression, caused by the closure of overseas export markets, limited much of the transportation benefit of an improved canal, but manufacturers saw the potential advantage of this new source of convenient power. By the 1850s they were buying up land on either side of the canal and building factories. One of the earliest entrepreneurs was John Redpath, who invested the profits of his real estate sales in a sugar refinery – the first of its kind in Canada, which until that time had had to import refined sugar. This and other factories along the Lachine Canal at mid-century launched Canada’s industrial revolution.

The Irish workers who figure so prominently on the 1820s Lachine Canal pay lists had established the area’s residential character. The later 1840s brought thousands of Irish families to Montreal, their numbers soon filling the ranks of the industrial working class. Most settled in the low-rent districts straddling the canal - Griffintown to the north, Point St. Charles and Victoria Ville (“Goose Village”) to the south.

The last area was the site of the quarantine “fever” sheds built in 1847 to accommodate the countless victims of typhus who arrived in far larger numbers than the city was able to cope with. Over a decade later, a mass grave containing typhus victims was discovered by workers laying the foundations for the Victoria railway bridge, which crossed the St. Lawrence River from a point at the edge of the Lachine Canal.

Sources

Newton Bosworth, Hochelaga Depicta, Montreal, 1839.

Yvon Desloges and Alain Gelly, The Lachine Canal, Montreal, 2002.

Gerald Tulchinsky, “The Construction of the First Lachine Canal, 1815-1826,” M.A. Thesis, McGill University, 1960.

Gerald Tulchinsky, “John Redpath,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography online.

John Witham, “Andrew White,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography online.

To Learn More

Lachine Canal - National Historic Site : The Course of History; Parks Canada www.pc.gc.ca

Author

Rod MacLeod is a Quebec social historian specializing in the history of Montreal’s Anglo-Protestant community and its institutions. He is co-author of A Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801-1998 (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2004); “The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalisation, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861” (Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 2003); “Little Fists for Social Justice: Anti-Semitism, Community, and Montreal’s Aberdeen School” (Labour/Le Travail, Fall 2012). He is the current editor of the Quebec Heritage News.

Add new comment