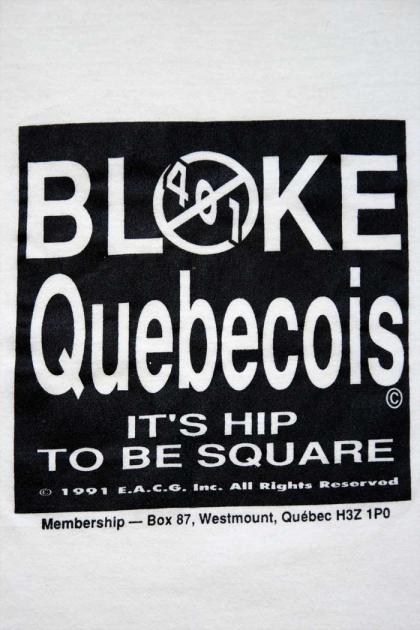

Bloke Quebecois T-shirt

Organization: Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network

Coordinates: www.qahn.org

Address: 400-257 Queen Street, Sherbrooke, QC J1M 1K7

Region: Montreal

Contact: Matthew Farfan, execdir(a)qahn.org

Description: T-shirt with inscription created by the “Bloke Quebecois” prior to the second referendum to indicate that Anglophones were here to stay – and to contribute.

Year made: 1991

Made by: Bloke Quebecois

Materials/Medium: Cotton

Colours: White with black inset image

Provenance: Quebec

Size: 70 cm long x 80 cm wide

Photos: Rachel Garber

Hitting the 401

Rod MacLeod

Among the world’s great migrations of peoples throughout history, the exodus of Anglophones from Quebec in the years following the Parti Québécois electoral victory in late 1976 ranks relatively high on the list – at least in terms of numbers: upwards of 200,000 people left the province over a 30-year period.

This exile was voluntary, of course, and partly based on the desire to seek greener pastures that is the mark of social mobility. For the most part, however, the people who left did so out of frustration over a society that had changed for the worse, in their eyes. They went, confident of finding more familiar and culturally comforting surroundings, especially in Toronto: “hitting the 401” (the main highway between Montreal and Toronto) became a euphemism for this exodus. People who stayed in Quebec tended to fall into two camps: those who wished to fight the changes and restore the old regime, and those who were willing to adapt.

Most Anglophones who were adults by the 1970s remembered a time when French was the language of the majority of people, but one could practically live one’s entire life without having to speak it – other than at school. Such people had lived through years of tension, including the threat of violence from radical separatist organizations, leading up to the October Crisis of 1970. Many felt sympathy for the aspirations of Francophones, whose language and culture were not always treated with respect. Such sympathy fell far short of understanding the desire for political independence, however.

The rise of the Parti Québécois (PQ) was viewed with alarm by many Anglophones, and when the PQ came to power they feared they would soon find themselves adrift in an unfamiliar new country. Some pulled up stakes as soon as they could. Others hesitated, and then discovered that the housing market was falling rapidly and it would become harder and harder to finance a move. Montreal’s loss was Toronto’s gain, culturally and demographically; the latter soon surpassed Montreal in population and took over its title as the metropolis of Canada. Fear of economic disruption caused by independence prompted most major companies to relocate their head offices from Montreal to Toronto, furthering the sense of decline in Quebec.

Other than fears of separation – partly assuaged after the defeat of the PQ’s 1980 referendum over sovereignty – what made Anglophones most uncomfortable was the language legislation. Most Anglophones were not directly affected by the provisions of the 1977 Charter of the French Language (“Bill 101”) that placed restrictions on who could attend school in English, but many criticized the Act’s impact on immigrants and the feared eventual obsolescence of English-language schools. A greater source of irritation was the Charter’s provisions that obliged businesses of a certain size to operate in French and required public signs to be in French only. The Office de la Langue Française, established in 1961, was mandated by the Charter to assess complaints against perceived violators of these requirements, earning the Office epithets like “language police” or “tongue troopers” from scornful Anglophones. Cases abounded of small businesses fined for displaying signs in English, of institutions such as Schwartz’s and Eaton’s forced to remove their signs’ apostrophes, and of menus criticized for listing “hamburger” instead of the newly-minted approved term hambourgeois.

Those who had altercations with the Office had greater incentive to hit the 401. Many of those who stayed took up the fight against the Charter’s sign provisions, often deliberately displaying bilingual or even unilingual signs to provoke a visit from the Office in the hopes that such cases would bring ridicule on a government that would enforce such measures. Alliance Quebec, an English-rights activist organization formed in the early 1980s, challenged the Charter’s provisions in court, resulting in some success, notably the Supreme Court’s 1988 decision that the prohibition of languages other than French on signs was a violation of freedom of expression. By that time, the PQ was out of power, and the ruling Liberal Party drafted Bill 178, which allowed for English on public signs so long as it was no more than half the size of any French text. To many, this was scarcely an improvement on the Charter’s original provisions, given that businesses were now obsessed with measuring the size of lettering on their signs. Another wave of Anglophone exodus ensued.

Parallel to the rights activism was a growing feeling among many Anglophones that such disputes over language, while absurd in their way, could be taken in stride as part of life in a province whose assets clearly outweighed its defects. An early manifestation of this spirit was the 1983 publication of The Anglo guide to survival in Québec, a compilation of cartoons and articles edited by journalists Jon Kalina and Josh Freed, with material from such well-known Quebec writers as Nick Auf der Maur, Mike Boone, Wayne Grigsby, Charles Bury, and Katie Malloch, as well as cartoonist Terry Mosher (aka Aislin).

The book pokes fun at the odder consequences of language legislation (Schwartz’s becoming “La Charcuterie Hébraïque de Montréal, for instance), but even more fun at Anglophones’ often desperate attempts to converse in French or simply find their way around east-end Montreal. A telling example of a Quebec reality is Freed’s classic dialogue in French between two people who eventually discover they are both Anglophone; a genuine desire to adopt French as Quebec’s common public language can have hilarious consequences.

This kind of light-hearted response to a potentially divisive situation was echoed in the early 1990s, a low-point in English-French relations in the lead-up to the second referendum on sovereignty, when an organization called “Bloke Quebecois” (“bloke” being a French slang term for Anglophone as well as a reference to the newly-formed federal political party, the Bloc Québécois) sold T-shirts which sported the phrase “It’s Hip to be Square” (derived from the popular term for an Anglophone, “tête-carrée” or “square head”) and a sign with “401” crossed out. The implication is that hitting the 401 was no longer an option; Anglophones were here to stay – and to contribute.

From the late 1980s on, and particularly in the wake of the 1995 referendum, Quebec Anglophones experienced a kind of renaissance. Writers and artists, and even to an extent filmmakers, embraced Quebec’s creative economy and worked openly in English without the fear some had apparently experienced years before that using the English language was somehow shameful.

Beginning with the Quebec Writers Federation Awards in the late 1980s and culminating in the founding of Blue Metropolis a decade later, Anglophone authors posited the idea that there was a distinct English-Quebec literary culture. Politics and language aside, it is tempting for any Quebec artist to take the 401 to Toronto, where the money is. To stay in Quebec – to stay at home – is an indication of much conceptual distance travelled from the days when blokes really had square heads.

Sources

Cool to be Canadian: http://www.cool.ca/cool_en/cooa1002s.htm

Josh Freed and Jon Kalina, editors, An Anglo guide to survival in Québec, Montreal, 1983.

Linda Leith, Writing in the Time of Nationalism, Winnipeg, 2010.

Garth Stevenson, Community Besieged: The Anglophone Minority and the Politics of Quebec, Montreal, 1999.

To Learn More

Grant Hamilton, “Going for Bloke in Quebec”, http://www.anglocom.com/documents/lectures/Going%20for%20Bloke%20in%20Qu...

David Johnston, “Here to Stay; The Hip Anglo,” Montreal Gazette, January 31, 2009. http://www.montrealgazette.com/business/Here+stay+anglo/1231646/story.html

M. Odile-Magnan, “To Stay or Not to Stay: Migrations of Young Anglo-Quebeckers,” Montréal: Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique (INRS) Urbanisation, Culture et Société, http://www.ucs.inrs.ca/pdf/RapportMagnanVersionAglaise050222.pdf.

Author

Rod MacLeod is a Quebec social historian specializing in the history of Montreal’s Anglo-Protestant community and its institutions. He is co-author of A Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801-1998 (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2004); “The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalisation, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861” (Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 2003); “Little Fists for Social Justice: Anti-Semitism, Community, and Montreal’s Aberdeen School” (Labour/Le Travail, Fall 2012). He is the current editor of the Quebec Heritage News.

Add new comment