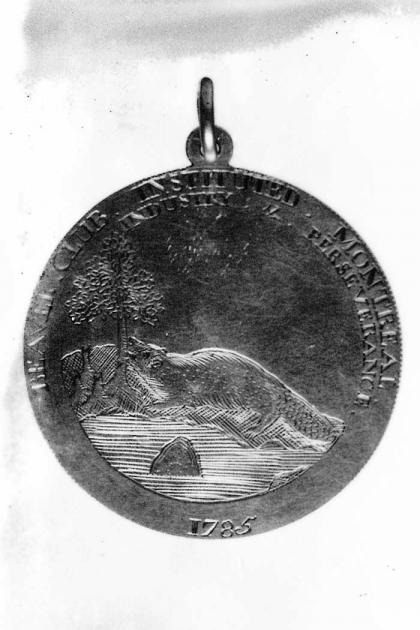

Beaver Medal

Organization: McCord Museum

Coordinates: http://www.mccord-museum.qc.ca

Address: 690 Sherbrooke Street West, Montreal, QC H3A 1E9

Region: Montreal

Contact: Cynthia Cooper, info(a)mccord.mcgill.ca

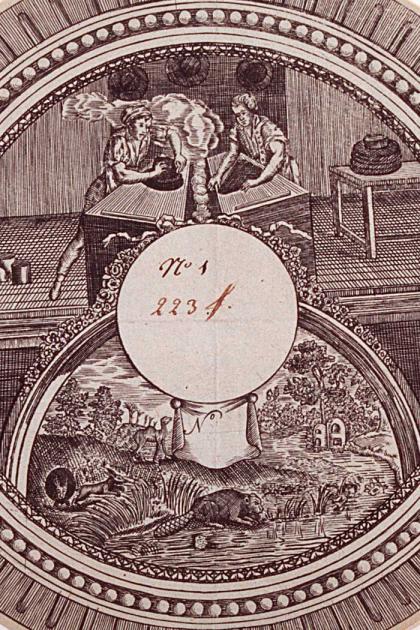

Description: (1, 2) Gold medals worn by members of the Beaver Club who were veterans of the fur trade and leaders of the North West Company. Front of the medal bears the inscription: “James McGill, Fortitude in Distress. 1766” Back: “Beaver Club. Instituted Montreal. Industry & Perseverance 1785” (3, 4) Print: Manufacture of Beaver Hats.

Year made: 1785

Made by: Unknown

Materials/Medium: (1, 2) gold; (3, 4) paper, ink

Colours: (1, 2) gold; (3, 4) black, white

Provenance: Quebec

Size: 3.6 cm

Photos: © McCord Museum, V-20853, V-02853.A, and M988X.6.

The Fur Trade

Rod MacLeod

The early history of Canada was shaped by fur. Nomadic peoples and farmers alike dealt regularly with the basic challenge of subsistence, but everyone depended on animals to survive the long winters. Natives tended to see the killing of fellow creatures as a solemn necessity, never taking the sacrifice for granted. Europeans were generally much less profound, seeing the faunal bounty of the Canadian landscape as a source of profit, mindful less of nature’s equilibrium than of an eager transatlantic market for fur.

The British via Hudson’s Bay and the French via the St. Lawrence Valley established trading networks into the North American hinterland. They relied on co-opted native hunters, a process that eventually destabilized the native population economically – and morally, given that ancient taboos were violated. Europeans also established outposts throughout the Northwest, making yearly journeys out with manufactured goods to sell, and back with canoes full of beaver pelts.

By the time New France fell to the British in 1760, French fur traders had formed a kind of mercantile aristocracy in Montreal society, but they were now cut off from their traditional markets in France. However, the British Empire offered vast new markets both overseas and in the thirteen colonies to the south. Enterprising British merchants made contact with the established French-speaking traders, forging alliances that were mutually beneficial, if ultimately to the newcomers’ advantage.

Ulsterman Isaac Todd and Scot James McGill each began working with French traders before forming their own partnership together. These two later joined forces with Benjamin and Joseph Frobisher, brothers from northern England who had made similar inroads throughout the North West and were ready to pool reserves of capital to dominate the fur trade.

A relative latecomer to this mix was Simon McTavish, a Scots trader based in New York who had made a small fortune stockpiling furs at the time of the American attack on Montreal at the end of 1775, when the city was cut off from its hinterland. McTavish now turned his focus to the North West and moved his operations to Montreal.

The American War of Independence forced these British traders to concentrate their energies on the commercial link between Montreal, its outposts, and Britain. In 1779, McTavish, the Frobishers, Todd and McGill launched a trading partnership that would eventually become the North West Company.

Gradually, these restless traders settled down. Like many newcomers wishing to attain social prominence, British merchants tended to marry into established French fur trading families: McGill married the widow of François-Amable Desrivières, while Frobisher and McTavish married two young daughters of the Chaboillez family. As family men, and especially as men of social standing and civic responsibility, the fur traders left their wild days in the bush behind them. They did let off steam, however, establishing the infamous Beaver Club as an excuse for drinking parties where alumni could sing voyageur songs at the tops of their voices, reputedly in a row with their legs around each other as if still in a canoe. These parties typically took place at the grand home of Joseph Frobisher, appropriately known as Beaver Hall.

Having made their fortunes, most Montreal fur traders acquired landed estates, typically on Mount Royal with views over the city and river valley. McTavish, by 1800 probably the colony’s richest man, decided to build a huge mansion on his estate, to be known as the McTavish Castle. One day, while supervising construction during poor weather, McTavish caught a fever and died. He was buried on his estate; his monument, rebuilt in the 1950s, can still be visited. The castle was abandoned, and stood for decades as a desolate and apparently haunted ruin.

McTavish’s Francophone widow took herself off to England along with her children, who all died relatively young. None of the other fur traders established lasting dynasties either. By 1820 there was little trace of these original fur traders in Montreal, and the North West Company began to flounder financially.

The Hudson’s Bay Company continued to flourish despite being much older (it had received its royal charter in 1670). The company’s jurisdiction extended from the northern part of what is now Quebec westward to the prairies, a territory known as Rupert’s Land which it controlled almost like a fiefdom. Even after formally ceding Rupert’s Land to the crown in 1713, the HBC continued to enjoy a trading monopoly over this region.

During the last part of the eighteenth century it experienced stiff competition from the North West Company, a rivalry that regularly turned violent. The NWC looked the stronger of the two companies right up to the time of the Napoleonic blockade of Britain, which made the British navy dependent on Canadian wood and obliged the government to favour timber over fur as a preferred import commodity. By that time, fur was essentially a luxury item – highly valuable, but less widely sought than in an earlier age. The chief fur product beloved by Europeans was the top hat, the mark of a distinguished and successful gentleman for at least another century. But the Canadian fur industry could not develop at the same rate it had done until that time.

In 1821, the British government forced the two companies to merge, but because of the leadership crisis at the NWC it was obliged to fold into the HBC. The new governor of the HBC was George Simpson, a feisty Scot who had worked his way up through the company and now presided over it like a cross between a modern CEO and a feudal lord.

Like the NWC Scots before him, Simpson eventually settled in the Montreal area: his headquarters was in Lachine, where he built a fine stone house near the old NWC warehouse. (Today the house is gone, but the warehouse is a National Historic Site.) With a vast fortune from fur, Simpson joined the Montreal business elite, investing heavily in banking and railways. He was one of the chief dignitaries welcoming the Prince of Wales to Canada in 1860, entertaining the royal party at his home in Lachine just days before his own sudden death. Prince Edward likely wore a top hat for this occasion, but it was more likely to have been made of silk than fur by this time.

The preference by the social elite for silk hats spelled the decline of the Canadian fur trade, along with the decline in beaver numbers. In 1870 the industry was deregulated. Rather than compete with upstarts, the HBC opted to be strategic and diversified, most famously into retail.

Sources

Gratien Allaire, “Charles-Jean-Baptiste Chaboillez,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.

François Béland, “Maurice-Régis Blondeau,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.

John Irwin Cooper, “James McGill,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.

John S Galbraith, “George Simpson,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.

McCord Museum, North West Company Collection, C104.

McGill University Library, Rare Books MS 431, 433, 434, 435.

Myron Momryk, “Isaac Todd,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.

Fernand Ouellet, “Benjamin Frobisher,” “Joseph Frobisher,” “Simon McTavish.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.

To Learn More

Sylvia Van Kirk, Many tender Ties: Women in the Fur Trade Society, 1670-1870, 1980.

Hudson Bay Company Heritage, http://www.hbcheritage.ca/hbcheritage/home

Peter C. Newman, The Company of Adventurers, 1985.

Jennifer S.H. Brown, Strangers in Blood, 1980.

In Pursuit of Adventure: The Fur Trade in Canada and the Northwest Company, http://digital.library.mcgill.ca/nwc/toolbar_1.htm

Author

Rod MacLeod is a Quebec social historian specializing in the history of Montreal’s Anglo-Protestant community and its institutions. He is co-author of A Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801-1998 (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2004); “The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalisation, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861” (Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 2003); “Little Fists for Social Justice: Anti-Semitism, Community, and Montreal’s Aberdeen School” (Labour/Le Travail, Fall 2012). He is the current editor of the Quebec Heritage News.

Comments

I have a Beaver Club Medallion dated 1785.

I also have a NWCo token dated 1820 which I wear around my neck. I am a direct descendant of William McGillivray, my lineage from the Metis twin Joseph born March 1, 1791 & my birthdate March 1, 1956. You can contact me at gilmcgillivary [at] gmail.com

Add new comment