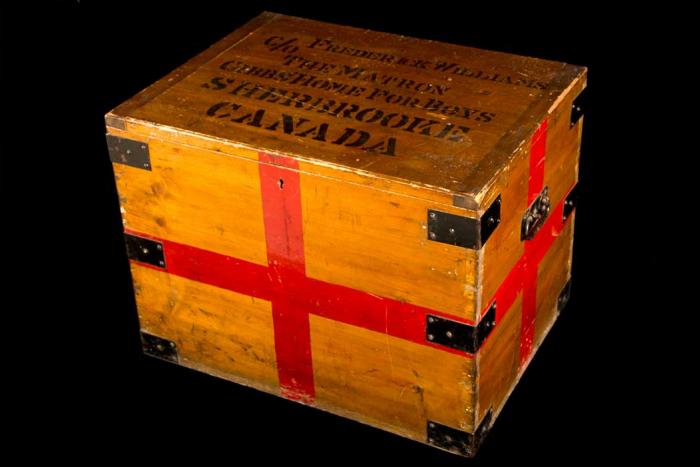

Home Child Box Organization: Missisquoi Museum Coordinates: www.missisquoimuseum.ca Address: 2 rue River, Stanbridge East, QC J0J 2H0 Region: Montérégie Contact: Heather Darch, info(a)missisquoimuseum.ca Description: Wooden “Home Child Box” used to transport the belongings of Home Child Frederick Williams from England to Canada in 1912. Year made: 1912 Made by: Unknown Materials/Medium: Pine wood Colours: Natural, red, black Provenance: England Size: 50 cm x 50 cm x 45 cm Photos: Rachel Garber. Courtesy Missisquoi Historical Society

Home Child Box

Heather Darch From the 1860s to the late 1930s, approximately 100,000 children were brought from Great Britain to Canada by religious and benevolent organizations. Children ranging in age from two to 17 years of age were sent to live with Canadian families to work as farm and domestic labourers in the burgeoning communities and farms across the country. Under the United Kingdom's “child migration scheme” which viewed child emigration as a solution to poverty, children were sent to live in Canada and other Commonwealth countries. While some were adopted by their host family, it was understood that they were here to be labourers for Canadian households and farms. These children were known as the “Home Children.”

The term “home children” derives from the institutional homes that sent children abroad to receiving homes that would then send them to farms or households. Social reformers of the 1860s were alarmed at the growing poverty and deplorable living conditions of Britain’s working poor. Overcrowding, poor sanitation, disease and hunger were the consequences of the industrial age. Children growing up in abject poverty were its hardest-hit victims. Reformers feared that at-risk children who lived in city slums and who had no access to religious instruction and schooling faced a future of immoral behaviour, poverty and substance abuse. They thought settlement in a country such as Canada which needed farm workers would alleviate the overcrowding in workhouses and teach children the value of hard work and making an honest living. Emigration was also an economical alternative to maintaining children in institutions.

Sending a child to Canada cost roughly the same amount as a year of caring for a child in an orphanage. The “scheme” was widely supported for years by Commonwealth governments, as it supplied much needed labour and population growth. While the premise of relocating poor children was based on good intentions, its results were often tragic. Some children were welcomed into families and were successful in creating new lives for themselves; others suffered ill-treatment and neglect at the hands of their employers and all experienced the sadness of separation from their family and home. The anguish and emotional scars resulting from being separated lasted a lifetime for children and their parents.

Although some children came directly from workhouses, very few of them were actually orphans. In fact most came from families who had placed their children in charitable homes as a convenient solution until fortunes turned for the better. Unfortunately, parental consent to a child’s emigration was often not obtained, and some parents were never officially informed of their child’s relocation. About one-sixth of the Home Children returned to Great Britain as adults, but the majority never saw their home and family again.

All Home Children were equipped with a wooden trunk that was packed with toiletries and clothing for the Canadian climate, as well as a Bible, a hymn book and John Bunyan’s “The Pilgrim’s Progress.” Some of the homes provided a small toy, but most children came without any personal objects. Children arrived by ship to Halifax, Quebec or Montreal, and from there travelled by train to receiving homes. Within weeks of their arrival, they were “distributed out” to farm families. Ideally, the receiving homes were to provide some level of supervision to ensure that their needs were being met. However, perhaps through a lack of funding and personnel, many children never had contact with the staff again. For some, this neglect by the receiving homes meant that abuse, loneliness and isolation went unchecked.

Among the approximately 50 agencies involved in relocation work in Canada, the Barnardo Homes is perhaps the best known. Under the direction of reformer Thomas Barnardo, one-third of the Home Children situated here came through his agency. In Quebec, nearly 7,000 children were transported to the Eastern Townships to receiving homes in Sherbrooke, Knowlton, Magog and Richmond. “The Gibbs Home for Boys” in Sherbrooke took in 2,064 children between 1886 and 1939. It had been established by the “Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge.” Mr. Thomas Keely, an officer of the society, supervised the placing and care of the children beginning in the early 1900s.

The Home Child box housed in the collection of the Missisquoi Museum was owned by Frederick Erasmus Charles Williams. He was born in Farnham, Kent, England on February 19, 1897 to Erasmus and Agnes Williams. He was not an orphan when he boarded the “SS Victorian” at the age of 15, along with 23 other boys. Everything he owned was packed into a lacquered pine box painted with a red cross on all four sides and stencilled with his final destination, the Gibbs Home, and in the care of “the Matron,” probably the long-serving Margaret MacIver. He arrived at Quebec on June 14, 1912, and was placed under the direction of Thomas Keely. Frederick Williams began working for Edward Knott as a farm labourer in West Shefford, Quebec, by the summer of that same year. The following year he was moved to Cowansville, Quebec, where he worked for Bruce Miner from 1913 to 1917.

On June 14, 1917, Frederick joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force and served as a gunner in the 7th Brigade Canadian Field Artillery. On his attestation paper, Frederick listed his home address as the Gibbs Home and his next of kin as Thomas Keely. Frederick died from Spanish Influenza on December 3, 1918, at the age of 21. He was buried in Valenciennes Cemetery, France.

It is interesting to note that during the first and second world wars, thousands of Home Children enlisted in the Canadian army and served their new country. Thomas Keely remained superintendent of the Gibbs Home until it closed in the 1930s. He turned the home into the “Gibb’s Club” to help the children keep in touch with one another. The home was sold in the 1950s, but until his death in 1969, Keely remained close to many of the children he had helped to cross the Atlantic.

Today more than 4 million Canadians are directly descended from the original 100,000 Home Children who landed on Canadian shores. The Government of Canada designated 2010 as the “Year of the British Home Child.” It officially recognized the hardships suffered by Home Children and their perseverance and courage in overcoming those hardships, and honoured the great strength and determination of this group of child immigrants who contributed to the building of Canada.

Sources:

Marjorie Kohli, The Golden Bridge: Young Immigrants to Canada 1833-1939, 2003.

Joy Parr, Labouring Children: British Immigrant Apprentices to Canada 1869-1924, 1980.

Gail Corbett, Nation Builders: Barnardo Children in Canada, 2002.

The Library and Archives of Canada, Attestation Paper of Frederick Williams Reference: RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 10387 – 54.

Canadian Museum of Civilization – Crossroads of Culture/Trunks and Travel/Barnardo Children, www.civilization.ca.

Missisquoi Historical Society collections re: Velma and Bruce Miner.

Pamela Jane Dillon, unpublished poetry, “The Suitcase: I pack my bag,” 2010.

Sarge Bampton, “The Home Children,” Townships Heritage Webmagazine, www.townshipsheritage.com

To Learn More:

Library and Archives Canada, www.collectionscanada.gc.ca

www.canadianbritishhomechildren.weebly.com

www.britishhomechild.com

Kenneth Bagnell, The Little Immigrants, 1980.

S.L. Barnardo and James Marchant, The Memoirs of the Late Dr. Barnardo, 1907.

Gail H. Corbett, Barnardo Children in Canada, 1981.

Marjory Harper, The Juvenile Immigrant in The Immigrant Experience, 1992.

Phyllis Harrison, The Home Children, 1979.

Margaret Humphreys, Empty Cradles, 1994.

Author:

Heather Darch is the curator of the Missisquoi Museum.