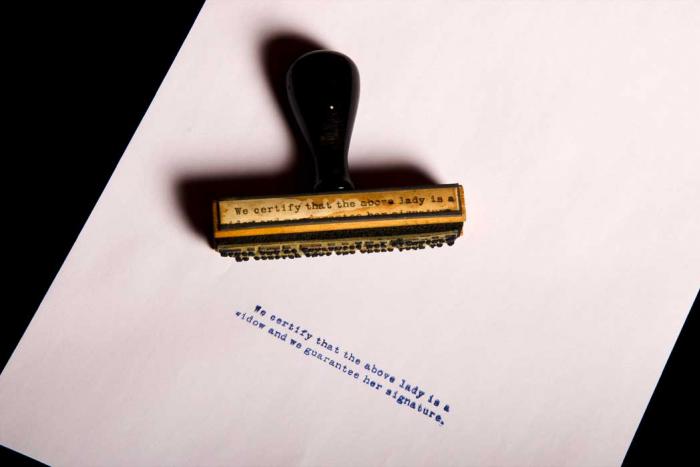

Rubber Stamp

Organization: Missisquoi Museum

Coordinates: www.missisquoimuseum.ca

Address: 2 rue River, Stanbridge East, QC J0J 2H0

Region: Montreal

Contact: Heather Darch, hdarch(a)museemissisquoi.ca

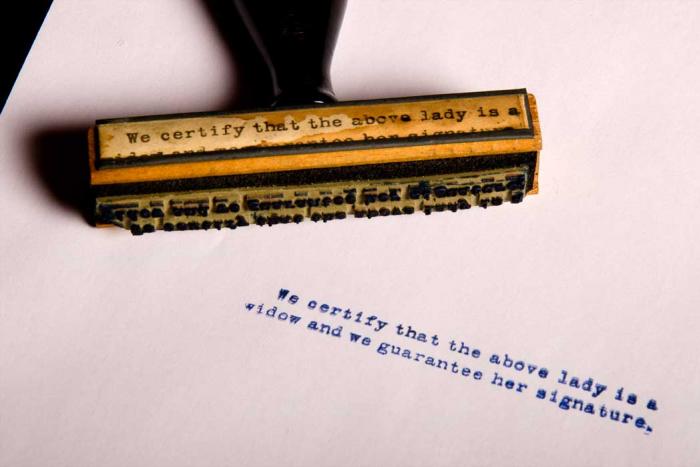

Description: Rubber stamp which reads “We certify that the above lady is a widow, and we guarantee her signature.”

Year made: circa 1950s

Made by: Walker & Campbell, 1033 Bleury St., PL 9188, Montreal

Materials/Medium: Wood, rubber

Colours: Natural, black

Provenance: Montreal, Quebec

Size: 9 cm x 2 cm x 6 cm handle

Photos: Rachel Garber. Courtesy Missisquoi Historical Society

Quebec’s Civil Code and Married Women’s Legal Status: 1866 to 1964

Cheryl Gosselin

In Quebec, married women were denied independent legal capacity to their civil rights until 1964. The Quebec Civil Code, imposed in the late 19th century on married women, made them subject to their husband’s control, as he was the undisputed head of the family household (Clio Collective, 1987). During this time, only unmarried women and widows could exercise their full civil rights.

The stamp which reads, “We certify that the above lady is a widow, and we guarantee her signature” signifies that a widow had the same legal rights as a man. She could, for example, own and sell property, obtain credit and have her own bank account, earn an income, dispose of her assets as she saw fit and was capable of entering and executing legal contracts. Married women were forbidden to carry out these rights unless their husbands consented and signed for their wives.

Between 1866 and 1964, Quebec women did not remain silent about their inferior civil status. As time marched on and their personal and public lives changed in step with the social and political contexts, married women demanded, on a number of occasions, freedoms from such oppressive restrictions. But it was not until 1964, with the passing of Bill 16, that married women’s legal incapacity was abolished and it was only in 1989 that they finally obtained total equality with their spouses.

By the same token, married women in English Canada were subject to oppressive circumstances under British Common Law. Marital unity meant that the wife’s property and person came entirely under the control of her husband (Prentice et. al. 1988). Pressure from women led to several amendments to the law, notably the Married Women’s Property Acts. Along with the more popular marriage regime of “separation of property,” by 1872, wives possessed more control over their assets and personal lives (Clio Collective 1987).

Quebec’s distinct and later trajectory can be understood by recognizing two factors. First, its Civil Code of 1866 was based on French Law, the Coutume de Paris which originally affirmed the subordinate status of married women when Quebec was a British colony (Clio Collective, 1987). Second, and most important, to make sense of why Quebec women had to wait longer to obtain their legal capacities in marriage, we must outline the nationalist question.

The ideology of Quebec nationalism strongly influenced gender relations and explains how married women in the province obtained their full legal status (Baillargeon, 2011). At the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th, traditional nationalists, composed of Catholic clergymen, politicians and intellectuals, were worried about the survival of their French-Canadian nation. A number of cultural, social and economic upheavals, including women’s waged labour, made them ponder solutions to protect the French language and way of life, along with the Catholic faith.

French Canadian mothers played an immense role in these nationalists’ plans to safeguard the Quebec population from what they perceived to be the surrounding Anglo domination of North America. Mothers were constantly told by the nationalists that their main duty in life was to marry and produce lots of babies for the nation. Nationalists feared that any tampering with matrimonial laws to give wives even the tiniest amount of legal rights would signal the death of French Canadians in Quebec.

Married women were not content to remain exclusively confined to the bonds of motherhood, however. In addition to their domestic roles, an increasing number of women worked for pay in the formal economy, elite and professional women were able to conduct their public and legal affairs without always having to obtain consent from husbands, and English-speaking women most likely were annoyed that their Canadian sisters had more liberal marriages than they did. It was not long before Quebec’s French and English women lobbied together for reforms to the Civil Code.

At this time changes were slow, but the first real feminist challenge to the civil statutes came in the form of an enquiry into married women’s rights (See Clio Collective 1987 for details). Known as the Dorian Commission, its final recommendations, released in 1930, were seen as a victory by many feminists. Yet, other women’s groups viewed the commission’s outcome as nothing more than a reinforcement of women’s disadvantages in marriage. While some changes were made, allowing women married in “community of property” unions more direct control over their earned assets, and wives in marriages “separate as to property” the ability to administer their own property, the principle of paternal power in the household was left intact (Ibid: 257-258).

Quebec women would have to wait until after the Second World War to see any substantial modifications to marital and family relations. At this time the famous Quebec feminist Thérèse Forget Casgrain, fought for and won, in 1945, the right of mothers to receive federal family allowance cheques instead of fathers.

Then, beginning in 1960, a series of socio-cultural upheavals marshaled in a new era of Quebec secular nationalism and state intervention in several sectors of society including the economy, education and social welfare (See Baillargeon, 2011). These societal transformations, commonly known as Quebec’s Quiet Revolution, expanded women’s opportunities in the public realm and laid the foundations for a renewed feminist consciousness which would later in the decade become the second wave of the women’s movement in Canada and Quebec.

Within this context, Marie-Claire Kirkland-Casgrain became Quebec’s first Member of the Legislative Assembly. In 1964, she instigated Bill 16 which ended married women’s legal incapacities. Finally, independence in marriage - no more authorizations from a husband before acting as her own person! (Clio Collective, 1987, p. 323).

Sources

Denyse Baillargeon, "Quebec Women of the Twentieth Century: Milestones in an Unfinished Journey," in Gervais, Stephan, Christopher Kirkey and Jarrett Rudy (eds), Quebec Questions, 2011.

Clio Collective (Dumont, Micheline, Michele Jean, Marie Lavigne, Jennifer Stoddart), Quebec Women: A History, 1987.

Sylvie D’Augerot-Arend, “Why So Late? Cultural and Institutional Factors in the Granting of Quebec and French Women’s Political Rights” in Journal of Canadian Studies, 26:1, Spring 1991.

Micheline Dumont, “The Origins of the Women’s Movement in Quebec, in Backhouse, Constance and David Flaherty (eds), Challenging Times, 1992.

Alison Prentice, Paula Bourne et. al., Canadian Women: A History, 1988.

To Learn More

Manon Tremblay (translated Kȁthe Roth) Quebec Women and Legislative Representation, 2010.

Andrée Lévesque and Yvonne M. Klein, Making and Breaking the Rules: Women in Quebec, 1919-1939, 2010.

Author

Dr. Cheryl Gosselin, a Townships native, has been teaching in the Department of Sociology at Bishop’s University since 1991. She teaches in the areas of gender studies, feminist social theory, Quebec society, urban sociology and ethno-cultural diversity. Her research focuses on Quebec’s women’s history, the socio-economic status of English-speaking women of Quebec and majority-minority relations in the province. Cheryl Gosselin also serves on the board of directors for Townshippers’ Association and the Quebec Community Groups Network.